from Sue Challis

Introduction

These notes are from initial research explorations of the value of collage both as an aid to problem-solving and as an extension to thinking and learning. They are also part of my unpublished PhD thesis (Maximising impact: connecting creativity, participation and impact in the qualitative evaluation of creative community projects: Coventry University, School of Geography, Environment and Disaster Management 2014).

I became interested in the potential for collage to become part of formative or summative evaluations following my attendance at a Higher Education Academy workshop on collage (Thinking Through Writing and Making, HEA Workshop, Staffordshire University, Stoke-on-Trent, 29 March 2012) when I experienced collage as a problem-solving technique, and through continuing contact with Alke Groppel-Wegener through the Tactile Academia blog, which explores the value of creativity as an aid to academic writing and thinking.

These brief exercises came from the need to formulate recommendations about evaluation strategies which would be feasible for small to medium-sized community projects in less formal or skilled contexts than my own research field trials. I was interested not only in the value of collage but also in the degree to which the method would engage participants outside of a group or creative project context. Participants were asked to complete a problem-solving collage at home and in an academic lecture. I have also included the collage activity which I took part in which prompted my interest in the technique as a research method. Although these are by no means formal research interventions and thus results are only indicative, they are recorded here to suggest the value of further research into the relationship of resistance or willingness to engage with creative techniques to other factors. These might include the type of activities, technologies and materials, the type of participants, and the contexts and skills of implementation. The examples below also suggest that willingness to engage with creative activity and its impact are related to prior experiences and self-narrratives.

Example 1 Collage as an aid to problem-solving

(six adult volunteers, examples from two feedbacks)

I asked six adult volunteers, chosen arbitrarily from my own neighbours and friends but excluding arts professionals, to ‘think of a seemingly intractable problem, work-related or personal, and make a collage while you are thinking about it’. I gave or posted them bags of very similar and random materials (images, text, textiles, stationery) to work on in their own time. For some participants, the task seemed very daunting and slightly odd. Two people returned the bag, both saying that they felt , ‘too un-artistic’ to attempt it by themselves. Four people made collages. I asked them to tell me or write a short account of the process, commenting on how they felt when doing it and what impact it had on their thinking or problem-solving. Figures 1 and 2 are examples of two collages; their makers’ comments follow; and Figure 3 is an example of my own work, made at a Higher Education Academy workshop on collage (Exploring Layers of Meaning, HEA Workshop, University of Chester, Chester, 26 March 2012).

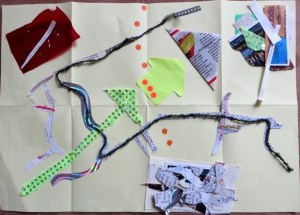

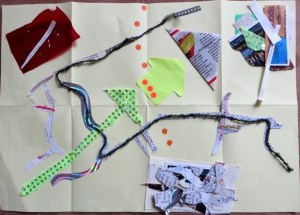

Figure 1 Problem-solving collage (A4 size)

(Participant 1, adult female)

Text 1

Comments on problem solving collage Figure 1 (above). Participant 1, adult, female.

Extract from email from participant 8.8.13, 22:23

“Subject: Re: Collage”

“The collage was about the assessment of the mental health of a teenager who is extremely vulnerable to sexual exploitation. She has been groomed/ lured by a paedophile ring and given drugs. She takes many drugs. She frequently threatens suicide. She is very verbally abusive to those who try to care for her because of her abuse in her own family of origin. The collage also deals with the response of organisations surrounding the girl and the difficulties in their relationships with each other. The hanged figure represents both the girl and another worker caught up on the turmoil surrounding her. The orange jagged line represents the panic. The Arabic script triangles/ shards represent the impossibility of putting our concern/ her situation/ our situation into meaningful language. The heads represent workers minds making different sense of her experience and our response to her experience. The blank spaces in the heads represent divided minds and the unknown of our own minds hidden from ourselves and from each other.

“Doing the collage helped me stand back from the situation and look at it differently. I had felt overwhelmed by the situation and by my feelings. The collage helped me feel more analytic. It also helped me see parallels between the girl and the worker, both of whom stir up my pity and also my frustration.

“As you know, I hung onto the collage bag for a long time before I felt I had a problem or could see how the collage might help. I was so challenged by this incident at work, which seemed impossible to resolve, that I thought I might as well do it, with no expectation of it working! The pictures and text which had meant nothing before I started to think about the issue seemed to become very relevant when I began to use them for the collage.

‘

PS you know I can bullshit at length!”

Figure 2 Problem-solving collage (A3 size)

(Participant, adult male)

Text 2 Comments on problem solving collage Figure 2, Participant 2, adult, male;

Extracts from researcher’s notes of informal interview 17.11.13

Researcher (R): How did you feel about the collage before you started it ?

Participant (P): I was reluctant to do this – I was ready to email you and say I wasn’t going to do it, then your reminder came…I don’t really have any problems to solve…I felt that it was a waste of time. I didn’t like the blank page of it, the open-endedness of it…I’m a non-arty person. I am not a person who does collage.

R: But you did do it in the end ?

P: Yes, the only way I could do it was, I put on some choral music which I like, I do listen to music sometimes but most of the time I am doing something purposeful…I had to have something else in my head to get going on it or it would seem like a waste of half an hour.

…

R: Can you describe your collage?

P: I chose the maps because I like maps and I made a river there, and the string follows the route because that’s how I measure my route on a map anyway…, the dots and maps had a meaning for me, I made the dots into arrows and each arrow gets bigger – that’s me deciding on a line, choosing a direction to go in in life and discarding the things that didn’t have meaning for me…

…

R: What interested you most about doing the collage?

P: Well… as I was, as I was trying to do it I found myself interested in the way I was selecting things, how I discard some things, like, I am someone who tries, and I try to persuade other people to do this too, to move on, to select a way forward and put the other possibilities, which we have decided not to do, onto one side, to discard them and move on. …So when I started this I realised that it was more about the process of how I solve problems than a particular problem, I discard the irrelevant stuff more than other people I think, then I don’t worry about it. It was like acting out something about myself. I had to decide, select what side of the paper I would keep and which bit discard or hide, it was all about selection…This became pleasurable when I had some idea of where I was going with it…

R: What are these two piles?

P: Well I , these are the things I didn’t want – the discard piles – I stuck them there, it’s only stuff I didn’t want, it might be important to someone else…As I was getting into it…I did start to enjoy doing it… I was thinking about myself, about getting somewhere, solving problems. I saw the solving problem part was about discarding what you don’t need and assembling a way forward, only in the abstract, honing down and selecting to get somewhere. I feel strong, it’s something that works for me… so I was mirroring what I do. When I got the idea of the map or journey I really did enjoy it.

R: Most people throw away the discards. You have stuck them on the collage. Was there a reason for that ?

P: Well, it’s…I suppose it’s because it’s not foolproof…the process of deciding to keep the discards… they are worth keeping, that’s my readiness to admit I’m wrong or go back and look at things again, other options. I think I’m visualising something, the process of keeping the discard, something about myself I hadn’t put into words really before…

Example 2 Collage as an aid to problem-solving (researcher’s own activity)

During the second year of my research I attended a Higher Education Academy workshop on collage (Writing in Creative Practice: Exploring Layers of Meaning, HEA Workshop, University of Chester, 26 March 2013) and made a collage myself which was a significant help in solving my own problem of making the transition from community arts practitioner to academic writer. This extract from a journal article written at the time (and subsequently incorporated into reflections in the Journal of Writing in Creative Practice) sums up the value of the collage to me, particularly the process of selection from random materials. As Butler-Kisber says: “Novel juxtapositions and/or connections, and gaps or spaces, can reveal both the intended and the unintended” (Butler-Kisber 2008: 269):

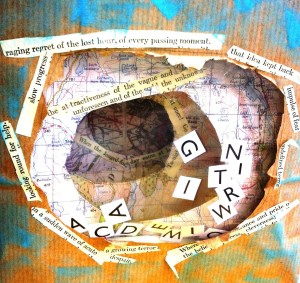

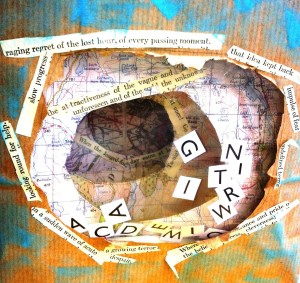

Figure 3 Problem-solving collage

(researcher – artist, adult female)

“I made a 3D collage bag (Fig 3) about my problems with academic writing. A phrase from the provided text sprang at me: ‘… that idea kept back …’ (I think from a Conrad story), and leafing through the collage materials I chanced upon a map showing the house I was born in: as the Quakers say, these two finds ‘spoke to my condition’, helped me understand my reluctance to commit to a genre of writing that seemed to obliterate me and strengthened my resolve to understand how writing might become both academic and creative.

“Specifically, to see the relevance of the …[creative]…process to the wider debate about academic writing and creativity, and, more urgently, to the tensions I embodied trying to understand where my own creativity sat in (what are for me) the arduous and sometimes opaque protocols of academic discourse. Although I had long been familiar with John Wood’s ‘Critique of the Culture of Academic Rigour’ (2000), encountering the Writing PAD project through a ‘hands on’ HEA seminar was the trigger for this: it gave me permission to regard my own creative activity as a way of knowing”.

Challis, S (2013: 189-190)

Example 3 Collage as a means to extend thinking time

(65 undergraduate, third-year Geography students, 15 Youth and Community Work students, Coventry University 2012 and 2013)

At the start of two, two-hour lectures entitled ‘Visual and creative research methodologies’ I gave each Geography student an envelope containing a similar range of collage materials (text, images, fabric, paper, scissors, glue) and explained that the intention was to explore the idea that concentrating on making a collage whilst listening to complex new ideas would support understanding (Butler-Kisber 2008).This activity was drawn from my own experience at the HEA workshop described above. While they worked in silence on their individual collage books (folded paper) I gave a lecture about a range of visual and creative methods, using digital slides, occasionally asking them to ‘look up now’. At the end of the session we discussed their experience and at the start of the second session (a week later) had a brief group discussion reflecting on its impact. I made notes from this discussion but there was no further follow-up as it was the last session of term in each case. This was by no means a satisfactory research exercise, having no means to measure changes in concentration or learning. However, as an activity suggestive of further research, I have included it here for its relevance to issues of resistance to and acceptance of creative methods, rather than the light it sheds on collage as an aid to thinking. Further research might include a questionnaire reflecting on self-reported change and feedback from other lecturers.

For Youth and Community Work students I was restricted to one two-hour session which was less formal (for example, sitting in a circle rather than in a lecture theatre). I introduced the session as above, but invited students to select collage material from a wide range laid out on a table. Students made collage books while I gave a presentation about visual and creative methodologies. The making was followed by a group discussion and some people shared their books.

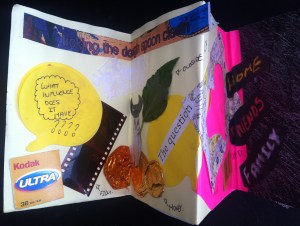

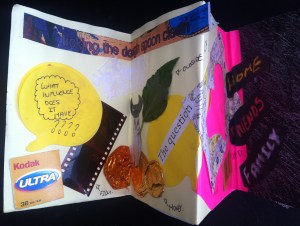

Figure 4 Collage made referring to content of lecture (A4 folded paper)

(Participant, geography student, male)

Text 3 Researcher’s observations from notes made after each Geography student session

(two sets of two, two-hours teaching sessions, with collage in first session of each set; November 2012, November 2013):

Some students made work clearly referring to the lecture content (Figure 4 ); these sometimes used text or phrases from the lecture or commented on it. For example, one male student made an image of his children learning “arts as well as sciences: I want them to have both to be whole people, not like me I just did sciences”, rather wistfully adding, “I haven’t got any children yet” (Researcher notes from group discussion). Others made collages clearly relating to feelings . A male student made a page, (Figure 5 ), with fierce concentration while listening to a video clip of a woman describing her experience of domestic violence. He commented: “I was feeling strong feelings while I was listening, it was quite upsetting really. I wasn’t really thinking about the drawing”. My interpretation of the drawing was that it reflected his turbulent feelings through colour and markmaking, and intensity through strength of physical gesture (pressure on page and over drawing). As such, it might offer a useful prompt to further discussion or thinking. In both classes a student stapled his finished book together and said that it was ‘private’. This could suggest that personal feelings had been expressed (although these may simply have been critical of the process or ‘rude’).

Figure 5 Made whilst listening to video clip about domestic violence (A5)

(Participant, geography student, male)

Mixed gender groups (marginally more female). In each group all but three students participated (five male, one female). There were varying degrees of willingness to take part. In the final discussions several students (about 5/35) said they found the process “useless”, “a distraction” or “pointless”; a similar number said it was “interesting”, “enjoyable” and they could “see the point”. In each session five people were willing to ‘share’, that is, show and talk about, their own collage, usually describing what it represented to them and how they felt making it. The people who shared made broadly positive comments about the activity (for example, that they ’enjoyed’ it). Six students (three in each group) said they felt that the activity had improved their concentration. In both groups several students said that they had been repeatedly told off in school for persistently doodling during lessons. They related doodling to a way of improving their concentration and ‘enjoyed’ the collage activity.

There was no way of telling if this activity did improve concentration, although the self-report of a small number of students might suggest so in some cases. However, as a ‘pilot’ for the method with a large group, including many adult males (missing from most of my previous research which was mainly with teenage boys and adult women) it was indicative: My informal observations suggested that more female students found it easier to attempt and to enjoy the activity, but I cannot be sure this was true without further research. More male students voiced their reluctance, but there could be many reasons for this. Resistance to participation was linked in discussion either to lack of commitment to qualitative methods (many of the students were using exclusively quantitative methods in their own research and had not used qualitative methods before), or to reluctance to do an arts-based activity because of lack of skill or experience. Where there was reluctance, I did not feel that it was the ‘open-endedness’ per se which was a barrier, rather a lack of belief in the usefulness of the method generally, or for themselves in particular.

Figure 6 Collage made expressing personal feelings (A5)

(Participant, youth work student, female)

The Youth and Community Work students (also mixed gender, mainly female) were generally more receptive to the collage making, and many of them in discussion could relate it to activities they might carry out in their own professional practice and qualitative research. They saw it much more as a prompt for discussion than an aid to concentration than the Geography students, although several did relate it to doodling as means of concentrating, and most said they ’enjoyed’ the activity. All students in this group shared their collage in the discussion: one student who had stapled his closed, explained this as an expression of specific feelings relating to self-disclosure rather than the activity. Several students in this group made collages about personal feelings unrelated to the lecture (Figure 6). On the whole, I felt that there was less resistance to the activity in this group; but again, this informal interpretation suggests a number of more specific lines of enquiry, about prior experience, current skills, gender, age, ethnicity and so on.

Tentative conclusions indicative of need for further research

In the first problem-solving collage activity, Example 1, participants expressed reluctance to participate connected with not regarding themselves as ‘artistic’ or being convinced about the method. I also think that a self-consciousness about participating in a ‘soft’, reflective activity underlies the comment in Text 1, ‘I can bullshit at length’.

In all cases, the extent to which participants identify themselves as ‘arty’ impacts on willingness to engage (‘I am not a person who does collage’ Text 2); as does prior experience of qualitative research methods. Gauntlett suggests that willingness to engage with creative activity and its impact are related to prior experiences and self-narrratives (Gauntlett 2011). There are perhaps a whole raft of other contingent and structural factors related both to personalities and context. These could be subject to research enquiry in a number of feasible ways.

However, I would suggest that in all the examples shown here, where there has been an engagement with the process, these impacts could be inferred from discussion and examination of the collages to be possible pathways for further research:

1. Contribution to understanding of self or problem solving not available by other means (Texts 1-3)

2. Expression of feelings in a different (not verbalised) way (Figures 5 and 6)

3. Figure 4 also suggests that collage is not necessarily a distraction from new learning. Combined with the comments in Text 2, I relate this to the physical process of selecting and discarding, combining and juxtaposing, in other words, to the embodied enactment of thinking.

Sue Challis

REFERENCES

Butler-Kisber, L (2010) Qualitative Inquiry: thematic, narrative and Arts-Informed Perspectives London, Sage

Challis (2013) Sketchbook Postal Exchange Journal of Writing in Creative Practice Vol 6 No 2 London, Intellect

Gauntlett, D (2011) Making is Connecting :the social meaning of creativity from DIY to knitting and YouTube to Web 2.0 Cambridge, Polity Press