In spring I was asked by Maarten Koeners, organiser of the Playful University Club, whether I would deliver my ‘Make Your Own Research Boardgame’ workshop online. And I have to admit that my initial, not really thinking about it response to this request was ‘No’ – I really enjoy being in the room, chatting with people about their process and ideas, suggesting adjustments, and to see people getting inspired by each other’s work. But then I was thinking about this some more, and decided to approach this from the regenring perspective – apart from all the things that the workshop (and myself) would potentially lose in an online format, were there things that it could gain? And there were two things that I always thought were unsatisfactory about the face-to-face workshop: that it has to follow a prescribed route, and that there is not enough time to really think about the different stages. I wondered whether I could come up with a format that could address these issues.

To explain, the workshop follows a ‘method’ that I have come up with for people (well, really this is targeted at academics) to take their research (either the content or the process – or possibly both) and to develop it in/as a board game format. Initially I had thought of this as focusing on an illustration that could be used as an academic poster using the board game as a visual analogy of the process. However, I have learned that a lot of people who have taken the workshop, have been really interested in exploring game mechanics to build a play experience that allows players to experience parts of their research in some way. In my ‘method’ I have identified four stages that participants should go through, but three of these don’t have to be done in a particular order. When I do the workshop in person, though (especially if it’s a short one, so up to a half day), it is easier to prescribe an order for these, so that everybody can do them at the same time. Otherwise it just gets too messy and confusing for people. But if I were offering stand-alone videos for each stage, then everybody could go through these stages in the order they prefer! So this would solve the problem of the prescribed route.

The issue of time is something that could also be addressed in an online format – if these are stand-alone videos, everybody can take as much time as they like. But what about having not stand-alone videos, but guided sessions instead? This could also allow more time, because instead of cramming all the time we have together into consecutive hours, say 5, I could carve these up into 5 separate sessions, with me delivering for half an hour, and then giving participants a day to find another half hour to individually work on their own projects. While they wouldn’t have to devote more time to it (although they could), this would allow people to have more time to ‘digest’ and reflect on each stage, rather than the “you now have 30 minutes to complete this before we move on” pressure that is going on in the workshop. So this would allow people to spend more time on it – or maybe just spend their time on it in a smarter way.

I decided to play with these two ideas a bit more, calling them the ‘basic’ version and the ‘intensive’ version.

The basic version would mean participants get access to videos, but not much else. They can go through the three stages in any order they like, and devote as little or much time to it as suits them. Because it would be stand-alone this would work best for people who are organised and self-motivating.

The intensive version would mean that participants sign up for a week long workshop, that is delivered as a little chunk each day. Each session ends with a task (completing a specific stage), and then the next session starts with a review of the work that has been done by everybody. This would mean that the group and scheduled sessions can work to motivate the participants, and because there is interaction between them, people will get varied feedback on their progress and might inspire each other.

Not bad as concepts for online versions of this workshop, I thought. I talked with Maarten about it, and he agreed that either of these might work, and he suggested the Playful University group to ask for volunteers to test the formats.

And this is how I recently spent two weeks testing the intensive format with seven volunteers. Two weeks, you ask… yes, because when we got to Thursday (when I talked about the putting it together stage), it was clear that people wanted a bit more time to develop their prototypes, so we took the joint decision to move our last session back a week.

This was not the only useful thing that I learnt…

- I realised if this is now online, this means it might be taken by people all around the world, so make clear what time zone you are scheduling your meetings in.

- Finding a way to share prototypes meaningfully is crucial if you want this interaction. (We tried it out within Teams, the Collaboration Space in the Class Notebook works well for this stuff, and it means that I can have the videos in the same space as the interactions, but I’m not sure that will be something I continue in, simply because the Team is linked to my home institution, so everybody else needs to be a ‘guest’, which give them less permissions and is a bit clunky.)

- Clarifying expectations is important. I thought I had been clear about a number of things (i.e. pre-workshop tasks and how and when I was going to post them, the importance of brainstorming) but not all of this was clear to everybody, so I need to become better at this.

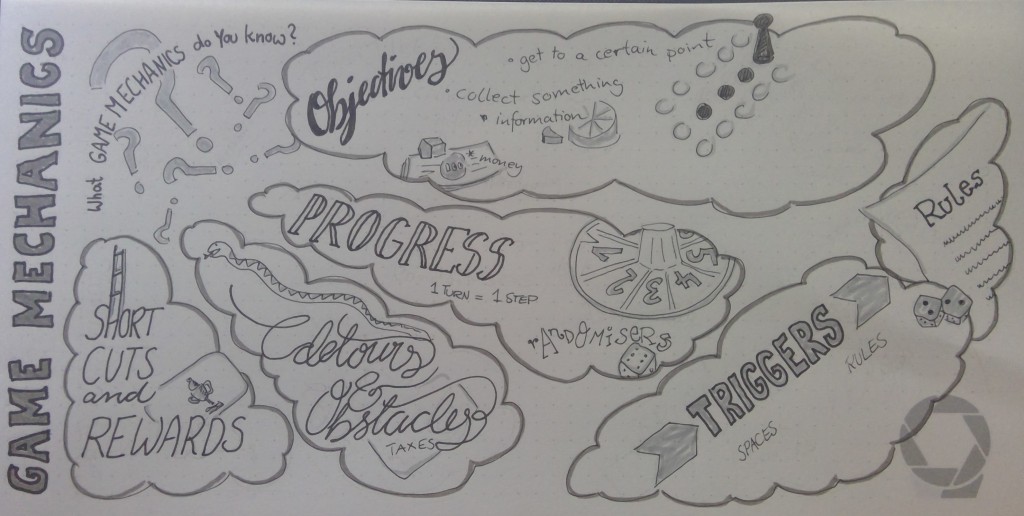

- Finding a way to present the instructions. I wasn’t sure how best to explain the stages. In a workshop in real life, I have things to show in order to explain what I am talking about. In this new format, I was wondering what way of presenting would make most sense and be most engaging… I’m still pondering this, but at the moment I am leaning towards talking through a sketchnote-type image, which could then also be shared as part of documentations that accompanies the workshop.

- Using examples. I am always in two minds about examples. I know they can be helpful, but they also tend to shape expectations and lead people in certain directions. If you show workshop participants too many examples of finished games, will they become frustrated by their own prototypes that are scruffy, because they are meant to be? Luckily my test participants have allowed me to use their work as examples in the future, so I will be able to share some in-progress images for any future iteration.

- Participant interactions. This is still something I also struggle in my regular teaching, now that it is online, the best way to facilitate an online discussion. With this test, I had tried to plan some time to interact with the group, but I hadn’t really planned for any way for them to interact with each other, apart from commenting on each other’s work. One session we brainstormed game mechanics together, and I found that very useful. One of the feedback points that came through was how much people liked those interactions and would have liked more of them, including introducing themselves to each other at the beginning. I had hoped that pre-workshop tasks would do some of that work, but then not integrated it into the workshop itself. Clearly if I want the ‘intensive’ version to be about working in a group, then this needs to be facilitated.

Overall this was a very successful experiment. Clearly there are things I want to change/tweak before taking the next step and offering either (or both) versions for sale, but I’m really happy with our week (and a bit), and we are planning another meet-up later in the year to see how prototypes have developed and maybe playtest with each other.

And some really amazing game prototypes were made, so this is definitely something that I want to pursue further, because it seems that an online version of this workshop does work!