As you will know if you are following this blog, last year I put together my own version of a guide to writing research essays (see Writing by Pictures), which I am currently revising for a proper release. Caught up in the excitement of this project, I don’t think I have ever really talked about WHY I thought it was important to do so. Yes, I wanted to collect the analogies and activities I do with my students in one place, but in a way this came out of a much larger context, which I am trying to tackle at the moment. I recently presented my initial thoughts at the Popular Culture Association/American Culture Association conference as well as the Writing PAD East Midlands Forum and thought I would sketch it out here, too, in case you are interested, but couldn’t make it to either of these meet-ups.

In my work my main challenge is to engage art and design students with academic research and writing. We are using a Writing in the Disciplines Approach, so these students are not doing something like Composition 101 with other subjects, as they might be doing as part of a liberal arts college in the US, for example, but rather they are in the cohorts that they spend most of their time with, which are very subject focused. I have some sessions with them in their first year (most of them in the first term), and I believe I give them the skills to research and write a pretty decent basic essay. Most of these students, however, I don’t see again after these encounters – other colleagues are taking over their contextual studies education. One class, however, I do see again in the second and also in their third (and final) year, and I noticed that they urgently need a refresher in all these skills. Of course the main issue here might be that they don’t have to write enough research papers to internalise these skills as part of an academic practice, but that is probably a different discussion (and also something that ultimately I probably won’t be able to change…). Anyway, so I was wondering whether there is an appropriate resource out there to teach or remind them of how to write an essay. And there are some very good books on this, but I could only find TEXTbooks, in the sense that they are predominantly made up of text. Occasionally you’ll find the odd diagram or cartoon, but most of them are very much text based.

This got me thinking about the textbook as a genre, and I came up with three pillars upon which the development of the textbooks that we know, use and, yes, also write are based on:

- An assumption that knowledge can (and needs to be) expressed in words (both spoken or written, but really better written) in order to be counted as ‘proper’ academic knowledge.

- The transmission model of education, which assumes that there is fixed knowledge that needs to be transmitted to the students, filling them up with it.

- And, maybe slightly overlooked in academic discussions on learning strategies and resources, the simple fact that when the textbook genre developed, printing technology had become very good at printing words (removable type and all that), but until fairly recently was very expensive when it came to reproducing quality images in large numbers.

Since this happened, however, a lot of development has taken place that has challenged all this. I would argue that while writing is still seen as a very good way to share insight, it is not considered the only way to develop your thinking. There has, for example, been a noted rise in the popularity of taking notes in non-written ways, which has come to the fore recently particularly through very popular publications in the business/management sector. Dan Roam argues in his Back of the Napkin series (my favourite is Blah Blah Blah, 2011) that words don’t work in some contexts, that drawing doesn’t mean you are ‘dumb’ but rather that we need ‘vivid‘ thinking, the visual and verbal working interdependently (Roam, 2011). Sunni Brown makes very similar points in her book The Doodle Revolution (2014), where she questions the usefulness of copiously written notes, that don’t really question the noted or put it into a personal context. Mike Rohde has developed the same problem into ‘sketchnoting’, which he states developed out of frustration with purely written notes (2013). Now, none of these people write for an academic context, but the success of their publications makes clear that the way to develop your thinking (which I would argue is actually quite crucial in an academic context) goes beyond the written word. While these books aren’t academic textbooks, they challenge the ‘three pillars of the textbook genre’, however, they are still pretty close to the familiar format of lots of text.

So I was wondering, are there any examples out there that go beyond this and that are aimed at an academic audience?

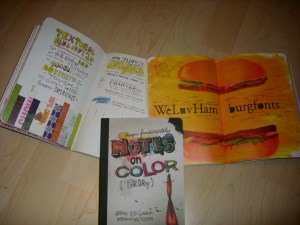

Rose Gonnella, Christopher J Navetta and (illustrator) Max Friedman have put together a series of books on Design Fundamentals (2013, 2014, 2015), and I would say that the contents of these books are very close to textbooks, but the presentation is very colourful and visual. The idea behind these books is that these are the notes your friend might give you if you have missed class. They include summaries and exercises of sessions, seemingly taped in, as well as the most important facts of the subject matter at hand.

The Good, the Bad and the Data (2013) is the second of Sally Campbell Galman’s Shane the Lone Ethnographer’s Guides. These are set out like comic books, with very simple black and white line drawings. They use the narrative device of Shane, the heroine, becoming the clueless student, asking all the questions we might ask about ethnography, and allowing us to go on a journey of learning with her.

Syllabus, Notes from an Accidental Professor (2014), by Linda Barry also has traces of a comic book in it, but then it is about a class for comic book students written and drawn by a comic book artist. This book has a very eclectic feel, simulating a yellow paper composition book popular in the US, and consisting of seemingly collaged together notes Barry made throughout her first few years of teaching a new course.

Unflattening (2015) is Nick Sousanis’ PhD thesis that was conceived in form of a graphic novel. It is a fascinating document that is a commentary on current educational practices, using the format of the graphic novel to make some very complex points in an incredibly elegant way.

While they are very different, and all of them have advantages and disadvantages, I think these four examples demonstrate that it is possible to redraw the textbook. While they all include linguistic knowledge, this is complemented – not just illustrated – by images more akin to a symbiosis. They are more inclusive in that they cast the reader in a role that makes you work for it – these are texts that need to be actively read in order to make sense of them, thus transcending the transmission model of education. They also use the current possibilities in printing, until quite recently none of them would have been able to be produced to this quality for a mass market.

A similar treatment might not be suitable for every subject discipline, but these examples show a way to open up the genre of the academic textbook and encourage us to redraw its rigid templates in order to allow our students to learn more effectively.

Do you know of any examples that should be included here?